How Designers Make Sense of the World

When someone eats your last Rolo, you feel a totally disproportionate sense of loss. It’s not about the chocolate. It’s about the gap. The narrative was broken.

Our brains crave closure like a moth craves light. This isn’t just artistic fussiness—it's biology. Our minds are pattern-seeking, problem-solving machines, evolved over millennia to find coherence in chaos and meaning in mess. If a final note I a piece of music doesn’t land, your brain is left holding a question mark—and it hates that.

Our brains evolved not to luxuriate in ambiguity, but to resolve it. Because in a prehistoric world, the inability to detect patterns—to spot the growl behind the rustle or the pawprint in the mud—meant you were likely someone else's dinner. Those who could see patterns in nature were able to predict and therefore survive. They planted and then harvested crops, and avoided sabre-toothed misunderstandings.

So, we became wired not just for survival, but for narrative. We became restless, creative creatures—itchy with the need to make meaning. We drew patterns in the dirt, scratched stories on cave walls, and eventually, designed complex systems, cities, and even shoes that glow in the dark. All of this because our brains, forever uncomfortable with uncertainty, keep asking, What happens next?

This forms the evolutionary imperative for creative thinking.

The Evolution of Design Thinking

Fast forward a few hundred millennia, and this evolutionary trait now powers a very particular type of mind: the designer’s mind. The so-called creative mind.

Design thinkers are not the same as other people.

Where others might see a door, a designer sees a threshold. Where others see a chair, a designer sees a metaphor.

Design thinking is not just a skill; it’s an attitude. Fundamentally different to straight-line deduction because it lives at the uncertain intersection of logic and creativity, intuition and strategy. Creative thinkers don’t just solve problems—they reframe them. They don’t just interpret the world—they shape it. The imperative is so strong that these principles are directed and redirected. It is almost irrepressible.

I trained as a theatre designer at Wimbledon School of Art. Truth be known, my first love is, and always will be, Theatre Design.

On leaving college, I began my working life at the National Theatre as a prop maker and then assistant to Jocelyn Herbert. I then designed various productions for theatre, ballet, opera and musical, domestically and internationally.

The only problem, I never made enough to live by.

Through friends from College, I gravitated into film and worked with a very young Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, before they became famous, on a film with the likes of the Pogues, Grace Jones, Joe Strummer, Jim Jarmusch, Dennis Hopper and Elvis Costello. A chance meeting with a former tutor from college introduced me to Bob Lush, and I began working at Richmond International for 5 years, designing some of Europe’s best hotels.

However, after 5 years, I figured I could run a design company on my own, so I set up CLA. Worked happily with my wonderful team for 25 years. I took on a business partner and, inevitably, we fell out, and we had to fold the company. That was 2019.

When the pandemic struck, and the world retreated indoors, I found myself—like many others—adrift. After 25 years running a design practice, I was suddenly out of the studio and into my own head. So, I did what any designer would do when faced with a crisis: I found a different solution, another outlet. I started sketching my local area. The act of drawing wasn’t about making pretty pictures—it was about stitching meaning into uncertainty. A way of holding onto a sense of self, place, and purpose when the world was spinning off its axis.

I began posting my drawings online, and to my surprise, they resonated. I became, inadvertently and accidentally, an author, illustrator, and self-publisher. My solution to uncertainty. Not because I set out to, but because the creative impulse drives the only sensible response to chaos and uncertainty. Designers make to make sense. When we can’t reinvent the world, we reinvent ourselves.

The Senses: Raw Data, Beautiful Noise

Our entire experience of the world begins with raw, chaotic data. Light bouncing off surfaces, sound waves flapping in our eardrums, textures pressing against our skin. It’s an undifferentiated mess—a mess until the brain gets involved.

We are not cameras, passively recording reality. We are more like a chef, grabbing whatever ingredients are to hand and whipping them into a coherent dish.

Meaning is not in the world. It is in us. We project it, filter it, shape it—just as a designer shapes a blank page or a raw space.

We don’t see the world as it is, but as we are.

And of course, we always think we can do it better.

The Brain: Chief Storyteller and Shameless Liar

The organ behind all of this is a jelly-like mass weighing approximately 1.5 kilograms, encased in a dark, silent box. It contains 86 billion neurons, and it has no direct contact with the outside world except through our senses. It uses 20% of all our energy. Which explains why Chess Grand Masters are usually thin. This is our brain.

Yet from this isolation emerges us, our identity, our sense of self. We connect with other brains, we imagine, and we dream.

Now, here’s the fascinating part: our brains are not just filtering reality, they’re also making it up. Our brains are glorious fabulists. We are master storytellers. There have been communities that didn’t invent the wheel, but there has never been a community that doesn’t tell stories and doesn’t gossip.

When faced with ambiguity, the brain doesn’t say “I don’t know.” It invents. It fills in blanks. It creates connections, correlations and stories that feel true, even if they aren’t.

Perhaps this is why conspiracy theories exist. Given a choice between “I don’t know why this happened” and “It’s probably the lizard people,” our minds often go with the more narratively satisfying option.

Designers and creative thinkers live on this knife-edge between truth and fiction. We build plausible futures. We make up new systems and then test them in the real world. Not deceivers (although that’s not always true)—rather, visionaries.

But the strategy is the same: the ability to craft stories from diverse fragments of events and experiences.

Pattern, Prediction, and the Pursuit of Meaning

The line between truth, reality, and falsehood is thin.

We do not see the world as it is; we see it as we are.

Culture evolves faster than biology. Yet human evolution is both biological and cultural.

At the heart of survival is pattern recognition and prediction. If you heard a rustling in the grass and knew that this might be a tiger, you could take evasive action. Learning (and perhaps survival) is understanding how one thing relates to another. It’s making the connections and correlations that yield meaningful patterns.

Pattern

We see patterns in everything. Pattern recognition is how we survive—and how we create. We are hard-wired for pattern.

Science and math are pattern recognition in nature.

Music is patterns of pitch, tone and time.

Decoration is often repeated symbols that collectively have meaning.

Language is symbolic, patterned sound imbued with meaning.

Pattern and Story are how we communicate. They are part of our DNA, a survival strategy.

Stories bind us into groups and communities; they transmit our values, teach us lessons. We are hard-wired for pattern recognition.

There has never been a society without stories. There have been societies without concrete, without Instagram, reinforced steel, and the wheel—but never without myth, metaphor, and narrative.

Stories bind us together. Religion, politics, sport, philosophies, and branding: all are stories built to explain existence and build communities and alliances.

Designers and creative thinkers manipulate these patterns and stories to create resonance. A material or colour choice becomes a tone of voice. A layout plan becomes a journey. A space becomes an experiential stage. To design is to orchestrate a pattern that unfolds across time, material, and emotion.

To design effectively is to manipulate experience through our use of narrative, materials, space and time.

Stories change the world.

Two Minds - One Head

Daniel Kahneman, Nobel laureate and behavioural psychologist, describes two systems of thought:

System 1: fast, intuitive, emotional. This is the gut instinct, the quick sketch, the sudden epiphany in the shower. Though often quieter.

System 2: slow, deliberate, logical. This is the detailed plan, the budget spreadsheet, the building code. The voice we hear loudest.

Designers are rare in their ability to use both fluently. They leap with System 1 and land with System 2. That leap-and-land behaviour is what allows designers to dream big and deliver. It also makes them more cognitively flexible—able to reframe problems, pivot strategies, and see opportunities others miss.

Creativity and the Adjacent Possible

If you imagine your mind or yourself as a sphere: a soapy bubble that contains your assumptions, habits, beliefs, memories, theories, biases, prejudices, stereotypes, explanations, etc..

The edge of this bubble is what biologist Stuart Kauffman calls "The Adjacent Possible" — the set of opportunities that are just one step away from the current state of a system, the immediate space of possibility lying just beyond current understanding.

Stepping into the Adjacent Possible is risky and requires the courage to face uncertainty.

Designers — by evolutionary and cultural imperative — are uniquely suited to this task.

The wider your mental bubble — the more diverse and open your references — the more adjacent possibilities you can access, and the more innovative you become.

By challenging assumptions, asking questions, and venturing into doubt, you find new connections, make new stories, and create new experiences that have meaning.

Creativity lives in the zone of uncertainty. It’s uncomfortable. It’s uncertain. It involves risk. A designer must step out of the zone of comfort and into the adjacent possible, into uncertainty.

Creativity begins not with answers, but with doubt and questions.

As Richard Feynman, one of my heroes, so elegantly said…

“I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing.

I think it is much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers that might be wrong....always remain uncertain…in order to make progress, one must leave the door ajar”

Now that we’ve leapt out of our bubble, let’s return to events and Story.

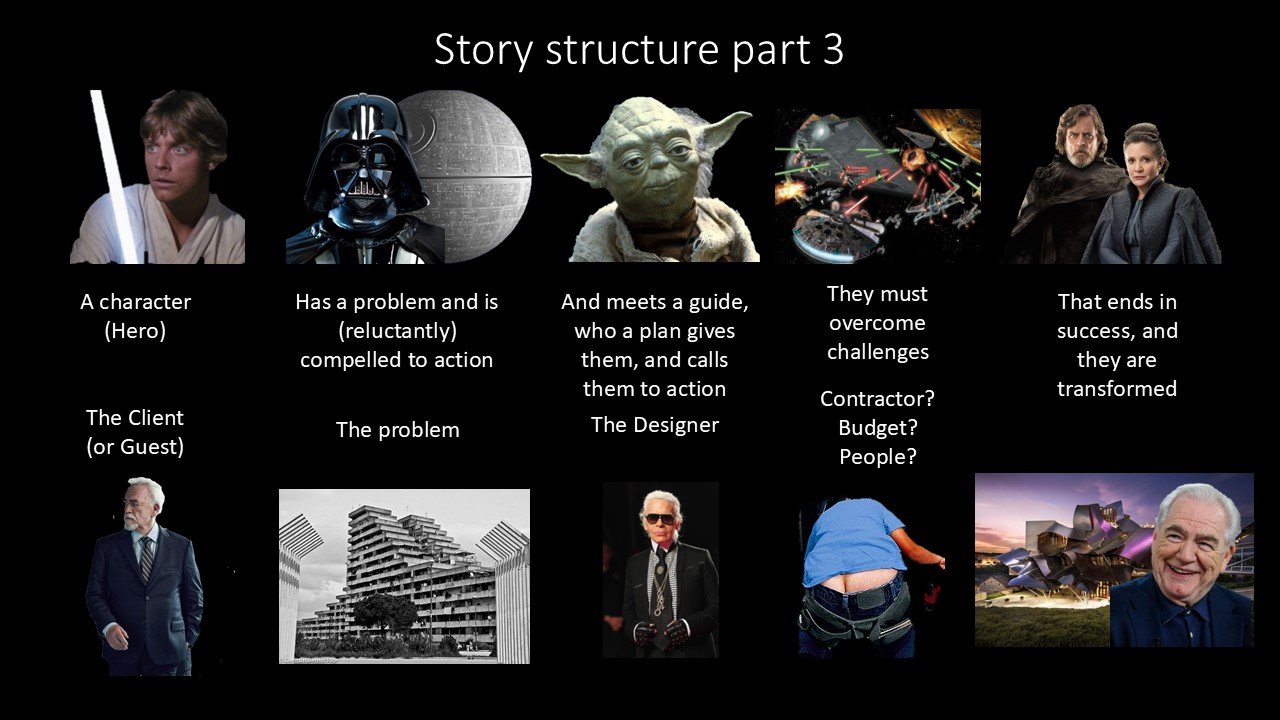

Every great story (or design) has at its heart a hero. But let’s be clear: the hero of your design project is not the designer, it’s the user, the guest, or the client.

Design - Story

As Donald Miller outlines in his StoryBrand framework, every compelling narrative has:

A character has a problem.

They meet a guide who gives them a plan.

They are called to action.

The character faces challenges.

The character either succeeds or avoids failure.

And the character is transformed.

From a design perspective.

The project is the problem.

The designer is the guide.

The brief is the call to action.

The design is the plan.

The Challenges are the constraints — spatial, economic, financial, and resource-based

The transformation is for the end-user, our character.

Great design follows a triple arc:

1. External journey – What users see and interact with.

2. Internal Journey – What they feel during and after the experience.

3. Philosophical journey – What the experience reveals about us, human nature or community, about who we are and what we value.

To succeed, designers answer three questions:

What does the hero want?

Who or what stands in their way?

What will their life look like if they succeed — or if they fail?

Creative thinking doesn’t just solve a problem—it tells a story. A story in which the user becomes a different version of themselves.

Three Layers of Design

Don Norman offers a brilliant framework for understanding design:

1. Visceral – The gut response.

2. Behavioural – How it works.

3. Reflective – What it means.

Great design touches all three. Think of an iPhone, a museum exhibit, or a Japanese tea ceremony. Each works across these levels—Visceral, functional, and meaningful.

Creative individuals also excel in divergent thinking: generating multiple solutions, irrespective of failure, rather than seeking a single "correct" answer.

Divergent thinking, in order to be successful, is open, expansive and free-flowing. Being playful with concepts and ideas has been shown to give rise to more creative solutions. Quantity plays an important part too. You can always discard ideas later; however, if you don’t express those ideas, you won’t know where they may lead.

Divergent thinking is characterised by Metaphor, Daydreaming, Visualisation, Playfulness, Humour, Non-linear, Imagination, Generalisation, Hunch, Intuition, Unconscious (gut) reaction.

Creative Thinkers as Architects of Change

I have used design as a very broad term covering all forms of creativity and creative minds. The ability to think differently, obliquely, is the instrument of change and is a quintessential human quality, rooted in pattern and story.

Design is the shaping of experience by the manipulation of meaning, the choreography of emotion and action.

To be a designer is to take on enormous responsibility and risk. Creative thinkers and designers influence how people feel, think, move, and relate. In the widest sense, they shape the world.

There is an evolutionary imperative to think creatively that we are all too often “educated” out of. Our systems prefer measurable outcomes, teaching what to think rather than how to think.

Design thinking teaches you something our societies rarely do – how to start over without fear. Perhaps that’s why creating feels healing – it reminds us that imperfect beginnings can still lead to beautiful outcomes. It is fear of failure that drives out our natural mode of thinking.

Design is an attitude. Design principles can be applied to anything. For me, it has been a journey through theatre design, film design, hotel design and now to book creation as author and illustrator.