Where Does Inspiration Come From?

I’ve always been fascinated by the moment an idea arrives — not the neat, tidy moment when it’s been polished and wrapped in ribbon, but the untidy, slightly breathless instant when something shifts in the mind and a new possibility becomes visible. Artists, writers and all creatives chase this moment, though it rarely comes when we demand it. It arrives like an unannounced guest, and often leaves just as mysteriously.

The Word and Its Breath

The word inspiration comes from the Latin inspirare — to breathe into. In the earliest sense, it meant divine influence, a god or muse literally breathing life into the mind or soul. Today, we use it to mean “the process of being mentally stimulated to do or feel something creative,” but I like that older, more physical sense of breath entering the body. It reminds me that inspiration is something that flows, something alive, and that our role is as much about receiving as it is about making.

Dylan Thomas captured this perfectly when he said, “I labour by singing light, not for ambition or bread.” It’s a line that contains both the effort — the labour — and the grace — the singing light. Inspiration isn’t just lightning; it’s the work of making something from it.

The Dance of Avoidance

But let’s be honest: there are days when the singing light never shows up, and instead we’re faced with the much more familiar figure of procrastination. I call it the dance of avoidance. We circle the work table, tidy our pencils, check the news, and make another cup of coffee. The studio or desk becomes a stage for all the tiny performances we put on to avoid actually starting.

Why do we do this? Because creating is risky. We have to step into the unknown and uncertainty. Starting means facing the possibility of not being good enough, of discovering the gap between the work we imagine and the work we’re capable of producing today. Avoidance is safer. But it’s also sterile.

We all have our own personal roadblocks: perfectionism, the lure of multitasking, and the belief that we need just a little more research before we begin. The trick is to learn how to step around them — or through them — without losing momentum.

In recent years, my strategy has been to identify the thing I am avoiding or putting off and to do that first. It amazes me how effective this is in prioritising the thing that needs to get done. Even as I sit writing this, I can see that my personal advance tax payment is overdue and needs attention.

Just Turning Up

One of the simplest, least glamorous truths about inspiration is that it visits those who are already working. The novelist Somerset Maugham once said, “I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately, it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

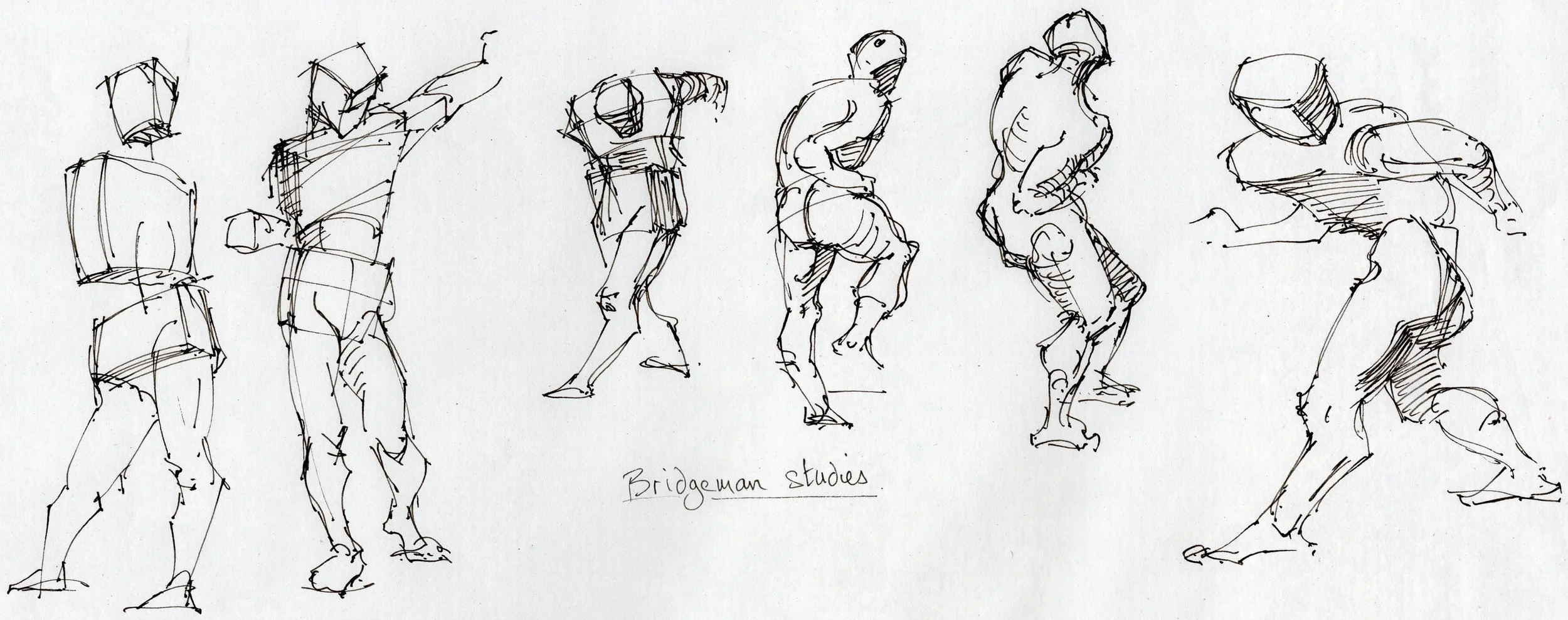

There’s research to back this up. A well-known study in a ceramics class divided students into two groups. One group would be graded purely on quantity — how many pots they produced. The other would be graded on quality — a single best pot. The quantity group, freed from the pressure of perfection, not only made more pots but also better ones. The act of making, over and over, refined their skill and deepened their creativity.

The lesson: inspiration thrives on action, not on waiting.

Finding Your Sources

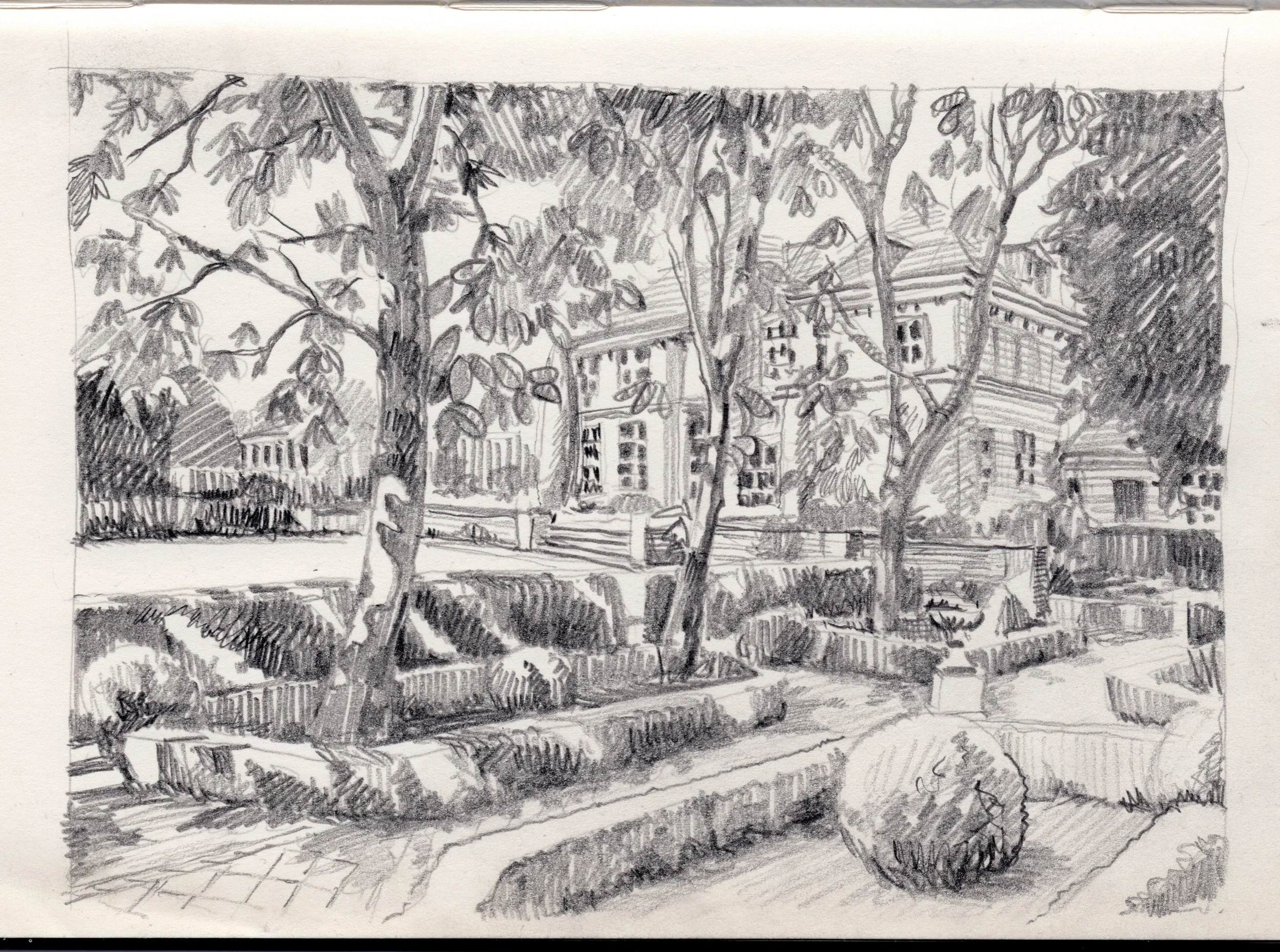

Still, there’s no denying that certain places, people, and experiences feed our creativity more than others. Some artists return again and again to the same stretch of coastline or the same street corner because something in it continually reveals new layers.

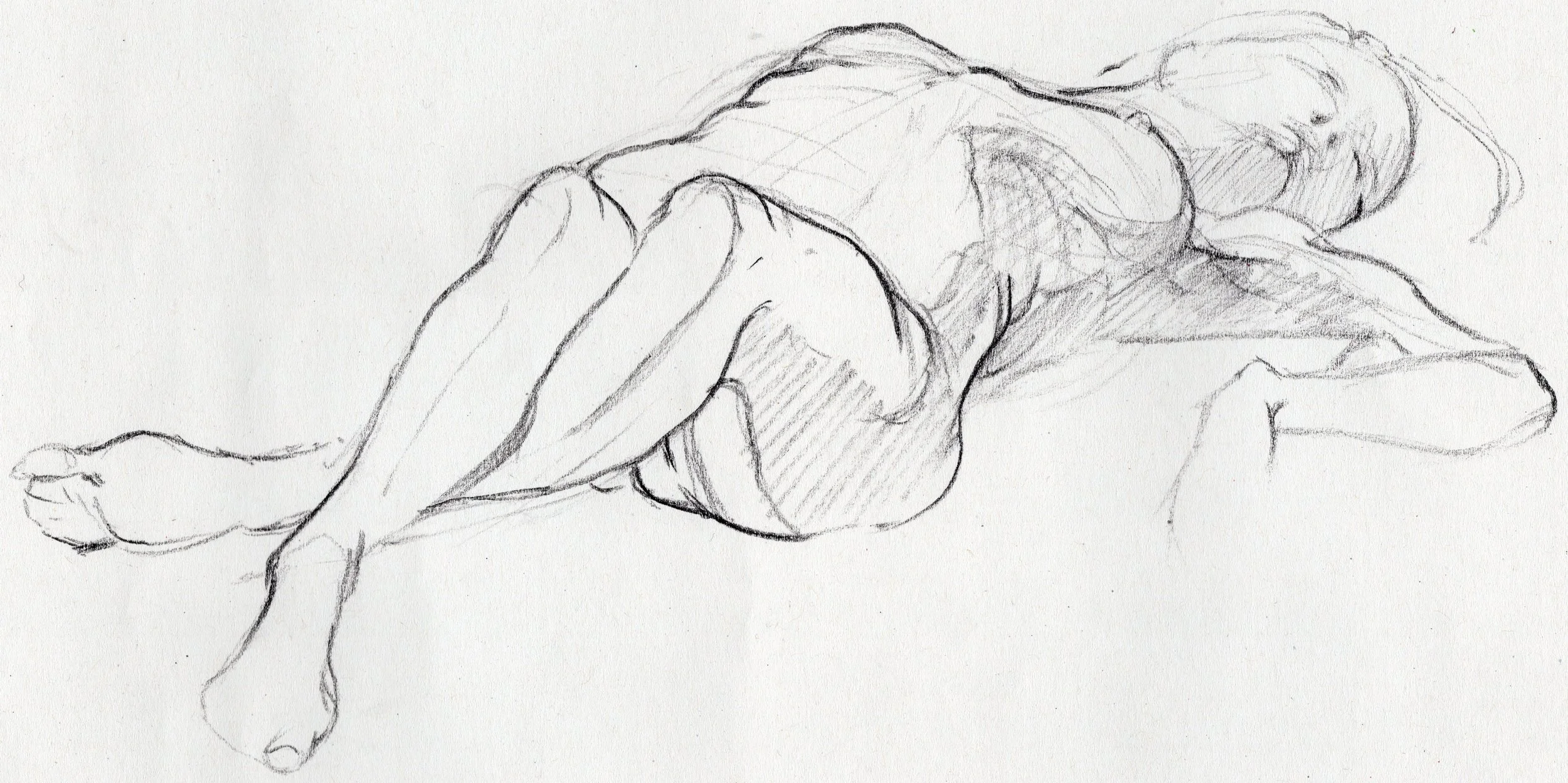

For me, inspiration often hides in the quiet margins: walking along a river in early morning, sketchbook in hand; overhearing fragments of conversation in a café; paging through old, foxed books in a second-hand shop. These aren’t grand events, but they open small windows in my mind. I’ve learned to notice what catches at the edges of my attention — the way light falls across a model's back, the rhythm of footsteps on cobblestones, the unexpected colour in a shadow.

As an illustrator, writer, or designer, you have to cultivate this habit of noticing. It’s a form of continuous reconnaissance: you’re always scouting for what makes your inner compass twitch. Some sources will fade over time, and new ones will emerge. The important thing is to keep the supply lines open. Quantity over quality. It’s also true that the more you look, the more you see.

The Myth of the Perfect Idea

There’s a persistent myth that inspiration has to feel big to be worth pursuing. In reality, many of the most enduring works begin with something tiny — a shape, a phrase, a fleeting sensation. The “adjacent possible,” as the scientist Stuart Kauffman calls it, is the set of ideas that are only one step away from what already exists. By exploring this space and stepping into uncertainty — not leaping toward some distant, perfect vision — we make steady, surprising progress.

The adjacent possible is like a door that opens onto a hallway, which leads to another door, and so on. The first step might seem unimpressive, but without it, you’ll never get to the unexpected rooms that lie ahead.

Balancing Effort and Openness

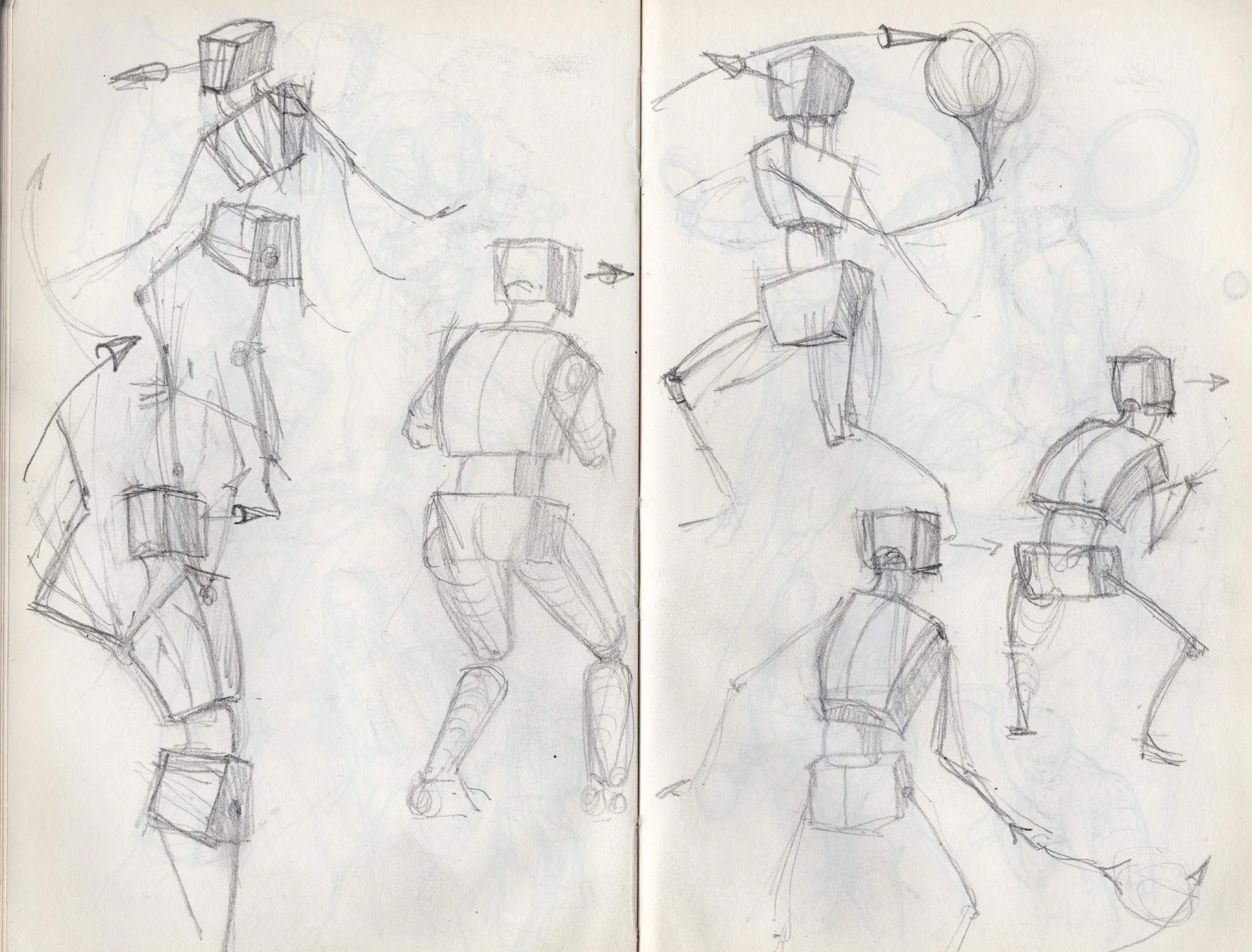

Inspiration lives in the tension between discipline and receptivity. Too much discipline and the work becomes mechanical; too much openness and nothing gets finished. The best artists and writers I know treat their creative lives like a tide: there are times to push out with focused work, and times to let the current carry them toward new material.

For me, sketching is one of the best bridges between these states. It’s deliberate, but it’s also porous — you can’t help but be affected by what you’re seeing, the angle of the light, the unpredictability of the street. The marks you make aren’t just records of objects, but of moments, thoughts, and sensations. They represent the choices you make as you observe and interpret.

Letting the Work Change You

One of the quiet gifts of showing up to work, even on days when you feel uninspired, is that the process itself will often shift your state of mind. You might begin resentfully, making marks without conviction, but somewhere in the doing, something shifts: a new line suggests a new form; a false start becomes the seed of a better idea.

This is the paradox: the work you begin without inspiration can become the work that inspires you.

A Practice for Inspiration

Over the years, I’ve developed a few simple practices to keep inspiration within reach:

Show up daily. Even 15 minutes keeps the channel open.

Work with intent. Make decisions about what you want to represent.

Seek variety. Change your routes, your materials, your vantage points.

Collect fragments. A phrase, a sketch, a colour palette — store them like seeds.

Review your own work. Sometimes the next idea is hidden in something you made years ago.

Protect time for idleness. Walk without purpose. Sit and watch the world. The breathing space matters.

Closing the Circle

Inspiration, in the end, is not a rare, divine lightning bolt — though it can feel that way. It’s more like weather: shifting, unpredictable, but responsive to the climate you create. The more you show up, the more you notice, the more you build conditions where inspiration can land and grow.

And when it does, when the singing light arrives, you’ll be ready — not just to receive it, but to labour with it, shaping it into something that didn’t exist before.