We live in an age of perpetual stimulation. Our phones buzz with notifications, our screens flicker with endless content, and our calendars overflow with commitments. The modern world has declared war on boredom, treating every empty moment as an emergency requiring immediate intervention. But in our frantic rush to fill every second with activity, we may be starving the very source of our creative power.

Recent neuroscience reveals what artists and thinkers have intuitively known for centuries: boredom isn't the enemy of creativity—it's the gateway. When we allow our minds to wander through seemingly unproductive stretches of time, we activate neural networks that generate our most innovative ideas. The question isn't whether we can afford to be bored—it's whether we can afford not to be.

The Neuroscience of the Wandering Mind

The dual-process theory of creativity suggests that creative thinking involves both spontaneous, unconscious processes of idea generation supported by the default mode network, as well as conscious evaluation and selection supported by the frontoparietal control network. This neurological dance between spontaneity and control represents the biological foundation of human innovation.

Research has demonstrated that creative ideas originate in the default mode network before being evaluated by other brain regions. When researchers dampened activity in specific regions of this network, participants generated significantly fewer creative solutions, while their other cognitive functions remained normal. This finding establishes that creativity fundamentally depends on the brain's resting-state network—the very system most active when we're doing nothing in particular.

Even more fascinating, recent studies have identified that mind-wandering provides mental breaks that relieve boredom while simultaneously enhancing creativity. The posterior cingulate cortex and angular gyrus—regions associated with creative coping strategies—show stronger activation in individuals with higher creative thinking ability. When we let our minds drift, we're not wasting time; we're activating the neural architecture of innovation.

Research linking ADHD with creativity found that deliberate mind-wandering, where people intentionally allow their thoughts to drift, was associated with greater creativity. This distinction between spontaneous and deliberate mind-wandering reveals an important truth: the quality of our mental downtime matters as much as its existence.

John Cleese and the Architecture of Creativity

Few people have thought as rigorously about creativity as John Cleese, the Monty Python legend who has spent decades studying the creative process. In his influential 1991 lecture, Cleese dismantled the myth of the creative genius, arguing instead for creativity as a mode of operating that anyone can access.

Cleese described creativity as requiring an open mode of thinking—relaxed, expansive, contemplative, and playful—as opposed to the closed mode we inhabit most of the time at work, which is active, anxious, and purposeful. The creative breakthrough occurs when we permit ourselves to step away from the pressure of immediate productivity.

Drawing on research by psychologist Donald MacKinnon, Cleese noted that the most creative individuals had acquired a facility for entering a particular mood, which MacKinnon described as an ability to play—a childlike capacity to explore ideas for enjoyment rather than immediate practical purpose. This playfulness requires psychological space that our overstimulated culture systematically denies us.

Cleese discovered that truly creative people learned to tolerate discomfort for much longer, putting in more pondering time before attempting to resolve problems. They resisted the urge to immediately close on a solution, instead allowing themselves to sit with uncertainty—a form of productive boredom that generates breakthrough insights.

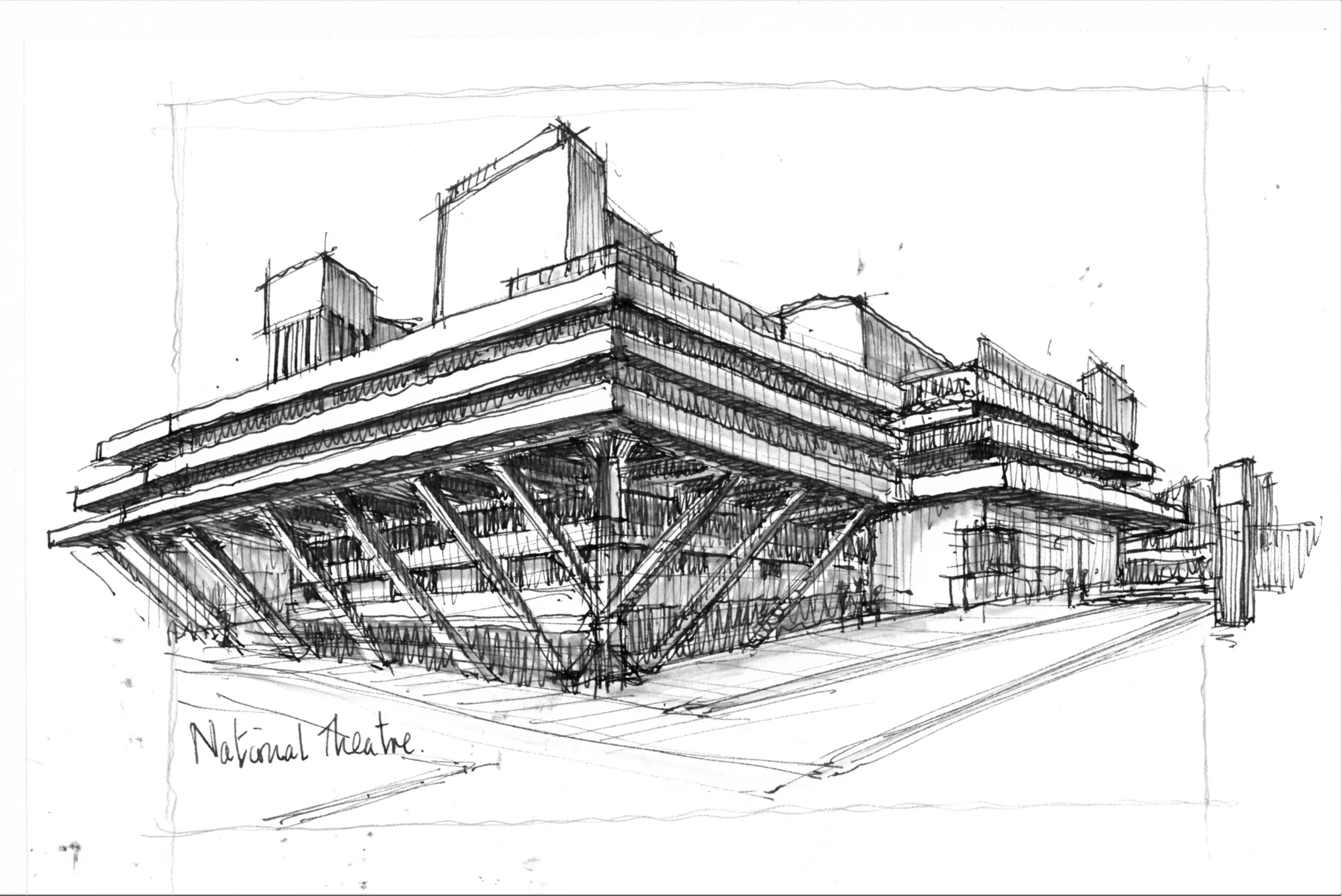

The comedian recommended creating what he called a space-time oasis: sealing yourself off from interruptions for a specific period, ideally ninety minutes, to allow your mind to shift from closed to open mode. In this protected interval, free from the tyranny of urgency, creativity can emerge.

The Flow State Paradox

The relationship between boredom and creativity might seem to contradict our understanding of flow states—those periods of intense, effortless concentration where we lose track of time and produce our best work. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described flow as occurring when challenge and skill are perfectly balanced, creating a state of complete absorption.

But flow and boredom are not opposites; they're complementary phases of the creative cycle. Boredom creates the conditions for the insights that fuel flow. The wandering mind during downtime connects disparate ideas, identifies interesting problems, and generates novel approaches. These insights then provide the material for deep, focused work.

Research examining creative incubation found that mind-wandering during breaks enhanced subsequent creative performance in writing tasks. The pause wasn't procrastination—it was preparation. The mind needs time to percolate before it can pour.

This cycle mirrors the experience of many creative professionals. A novelist might spend an afternoon staring out the window, apparently doing nothing, before suddenly sitting down to write thousands of words in a focused burst. The "doing nothing" wasn't separate from the productive writing—it was the essential precondition.

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

Betty Edwards' groundbreaking book "Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain" offers another perspective on accessing creativity through altered states of consciousness. Edwards argued that learning to draw isn't about developing hand skills but about learning to see—specifically, learning to shift from our usual left-brain mode of symbolic, verbal thinking to a right-brain mode of visual, spatial perception.

This shift requires what Edwards called "getting into R-mode"—a state remarkably similar to Cleese's open mode. It's contemplative, timeless, and non-verbal. And crucially, it requires stepping away from our default, busy-minded state. The pressure to be constantly productive keeps us locked in left-brain mode, unable to access the perceptual and creative capacities of the right hemisphere.

Edwards developed exercises designed to frustrate the left brain—like drawing upside down or focusing on negative space—forcing students into a different mode of perception. But perhaps the simplest way to access R-mode is through what appears to be its antithesis: doing absolutely nothing. When we stop filling every moment with purpose-driven activity, we allow different modes of consciousness to emerge.

The neuroscience supports this intuitive understanding. The default mode network—our resting-state system—doesn't simply switch off when we stop focusing on external tasks. Instead, it activates differently, engaging in what neuroscientists call spontaneous cognition: memories, imaginings, and creative associations that don't occur when we're narrowly focused on specific goals.

The Tyranny of Productivity Culture

Our cultural obsession with productivity has created a creativity crisis. We celebrate being busy, glorify the hustle, and treat downtime as laziness. Calendar apps optimise our schedules to eliminate gaps. Productivity gurus promise to help us achieve more in less time. Every moment becomes an opportunity for output, measurement, and achievement.

But research demonstrates that daydreaming offers more than just mental escape from boring tasks—it has a positive, simultaneous effect on task performance. The breaks we consider wasteful are actually cognitive necessities.

The irony is profound: in our rush to maximise productivity, we're undermining the very capacity for innovation that drives genuine progress. We're so busy executing existing plans that we never generate new ones. We've optimised ourselves into creative poverty.

Modern technology amplifies this problem exponentially. Every moment of potential boredom—waiting in line, commuting, sitting in a doctor's office—becomes an opportunity to check social media, respond to messages, or consume content. We've created a world where genuine mental downtime has become nearly impossible.

The Cognitive Cost of Overstimulation

Studies exploring state boredom versus trait boredom found that temporary experiences of boredom can prompt creative thinking and novel problem-solving approaches. But when we eliminate all boredom from our lives, we eliminate this creative catalyst.

The problem extends beyond lost opportunities for creativity. Constant stimulation trains our brains to expect and require continuous novelty. We develop shorter attention spans, reduced tolerance for difficult problems, and an addiction to the dopamine hits of new information. We become less capable of the sustained, deep thinking that produces meaningful insight.

The default mode network requires periods of low external stimulation to function optimally. When we constantly bombard ourselves with information and entertainment, we suppress this network's activity, reducing our capacity for the internally-directed attention that generates creative ideas.

As Cleese emphasised, nothing stops creativity as effectively as the fear of making a mistake, and humour helps us shift from closed to open mode faster than anything else. But both playfulness and acceptance of failure require the psychological space that constant busyness denies us.

Reclaiming Creative Downtime

The solution isn't to romanticise boredom or to artificially engineer tedious experiences. Rather, it's about reclaiming permission for unstructured time—moments when we're not consuming content, not producing output, not optimising anything.

This might mean taking walks without podcasts, sitting in cafes without phones, or simply staring out windows. It means resisting the cultural pressure to fill every gap with purposeful activity. It means recognising that time spent apparently doing nothing may be the most productive time of all.

Cleese advised keeping your mind resting against a subject in a friendly but persistent way, trusting that your unconscious will eventually provide a reward—a new thought that mysteriously appears. This gentle, sustained attention differs radically from the forced, deadline-driven focus that dominates most workplaces.

Creating these conditions requires intentionality. We might establish technology-free periods, protect creative time from meetings and messages, or simply permit ourselves to occasionally accomplish nothing. The specifics matter less than the commitment to preserving mental space.

Organisations can support this by rethinking productivity metrics, creating spaces for contemplation, and acknowledging that not all valuable work produces immediate, measurable outputs. The most innovative companies already understand this, providing employees with time for exploration, play, and apparently purposeless tinkering.

The Creative Necessity of Emptiness

Perhaps the most radical implication of creativity neuroscience is this: empty time isn't empty. When we allow our minds to wander, we're not wasting our cognitive resources—we're deploying them in ways that focused attention cannot achieve. The default mode network processes our experiences, consolidates memories, makes unexpected connections, and generates the insights that drive innovation.