What Your Designer Brain Is Really Doing

You know that moment when a solution arrives in the shower, fully formed, like Athena springing from Zeus's head? Or when you've been staring at a problem for hours and suddenly—click—everything makes sense? That's not magic. That's your brain doing something simultaneously elegant and absurd: questioning everything it thinks it knows.

Here's the delicious irony: our brains evolved to avoid the very thing that makes us creative. As neuroscientist Beau Lotto points out, our brains evolved toward certainty while simultaneously evolving away from creativity. Think about it—if your ancestors spent too long wondering whether that rustling was a predator or just the wind, well, you wouldn't be here to ponder the question. Creativity starts with uncertainty, not with answers, which means every genuinely creative act requires us to unlearn millions of years of evolutionary programming.

No pressure.

Creativity vs. Talent: Let's Get This Straight

Before we dive deeper into the neural mechanics, let's clear up a persistent confusion. Creativity and talent are not the same thing, though they're often conflated at dinner parties and performance reviews alike.

Talent is what you've got—an aptitude, a knack, perhaps even an innate facility for certain skills. Some people can carry a tune without trying. Others have spatial reasoning that makes Tetris look like child's play. Talent is your starting equipment.

Creativity, on the other hand, is what you do. It's the ability to generate novel and useful ideas by making unexpected connections between disparate concepts. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who spent decades studying creative individuals and developed the concept of "flow," emphasized that creativity requires both originality and value—it's not enough to be different; you must be meaningfully different (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). You can be talented without being creative (think of the technically flawless but emotionally dead musical performance, as with Abba Voyage which I recently went to see), and you can be creative without exceptional talent (ask any resourceful parent who's ever improvised a birthday party from household items).

The designer's brain, specifically, operates in this creative space constantly—not because designers are necessarily more talented, but because they've trained themselves to inhabit uncertainty and make it productive.

The Default Mode Network: Where Ideas Go to Play

Recent neuroscience has revealed something extraordinary about how creative breakthroughs actually happen. Research published in BRAIN in 2024 using advanced electrode imaging showed that creative ideas originate in the default mode network before being evaluated by other brain regions. The DMN—that sprawling network active when you're daydreaming, mind-wandering, or staring into space—lights up first during creative tasks. Then it synchronizes with regions responsible for complex problem-solving and decision-making.

Think of your DMN as the brain's improv troupe—it throws out wild ideas without editing. "What if chairs could fly? What if cups were sentient?" (I have “WHAT IF” on a post It note stuck to my screen). Then the executive control networks, your brain's sensible stage managers, step in to evaluate: "Okay, flying chairs are impractical, but chairs that fold flat for storage? That could work."

Antonio Damasio, who directs the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC, has spent decades demonstrating that emotions play a central role in social cognition and decision-making. In his groundbreaking work, Damasio argues that rationality is shaped and modulated by body signals, placing feelings at the heart of our highest reasoning abilities, including creativity. This upends centuries of Western philosophy that treated emotion as reason's antagonist. As Damasio writes, the biological feedback loop of feelings and emotions gives rise to our capacity for problem-solving, poetry, beauty, transcendence—everything we call creativity.

Your body, it turns out, is not a meat-vehicle (see “they’re made out of meat” by Terry Bisson) for your brilliant brain. It's an integral part of the creative process itself.

The Designer Brain: Trained to See Differently

So what makes a designer's brain function differently from the average person's? It's not a different organ—it's a differently trained one.

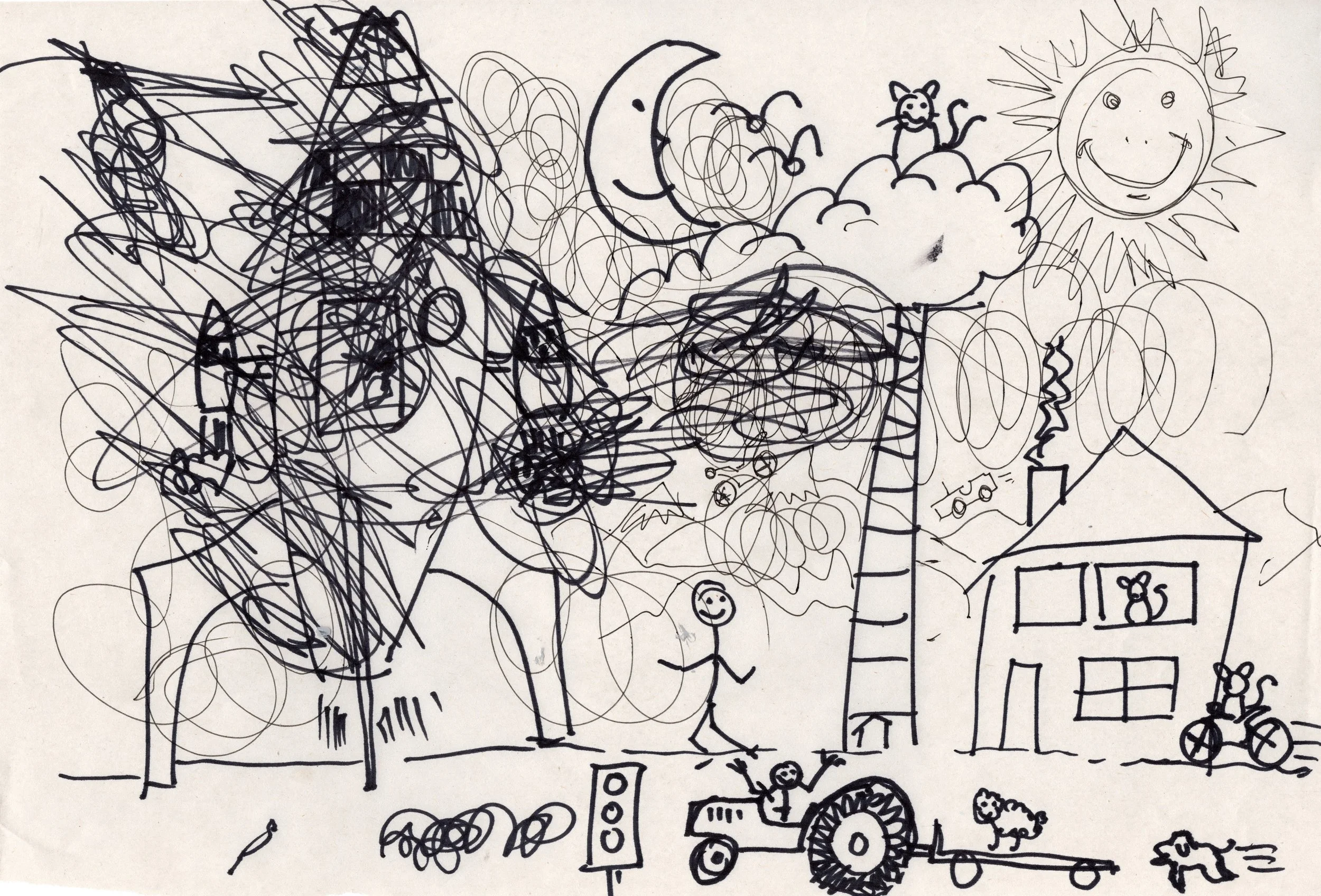

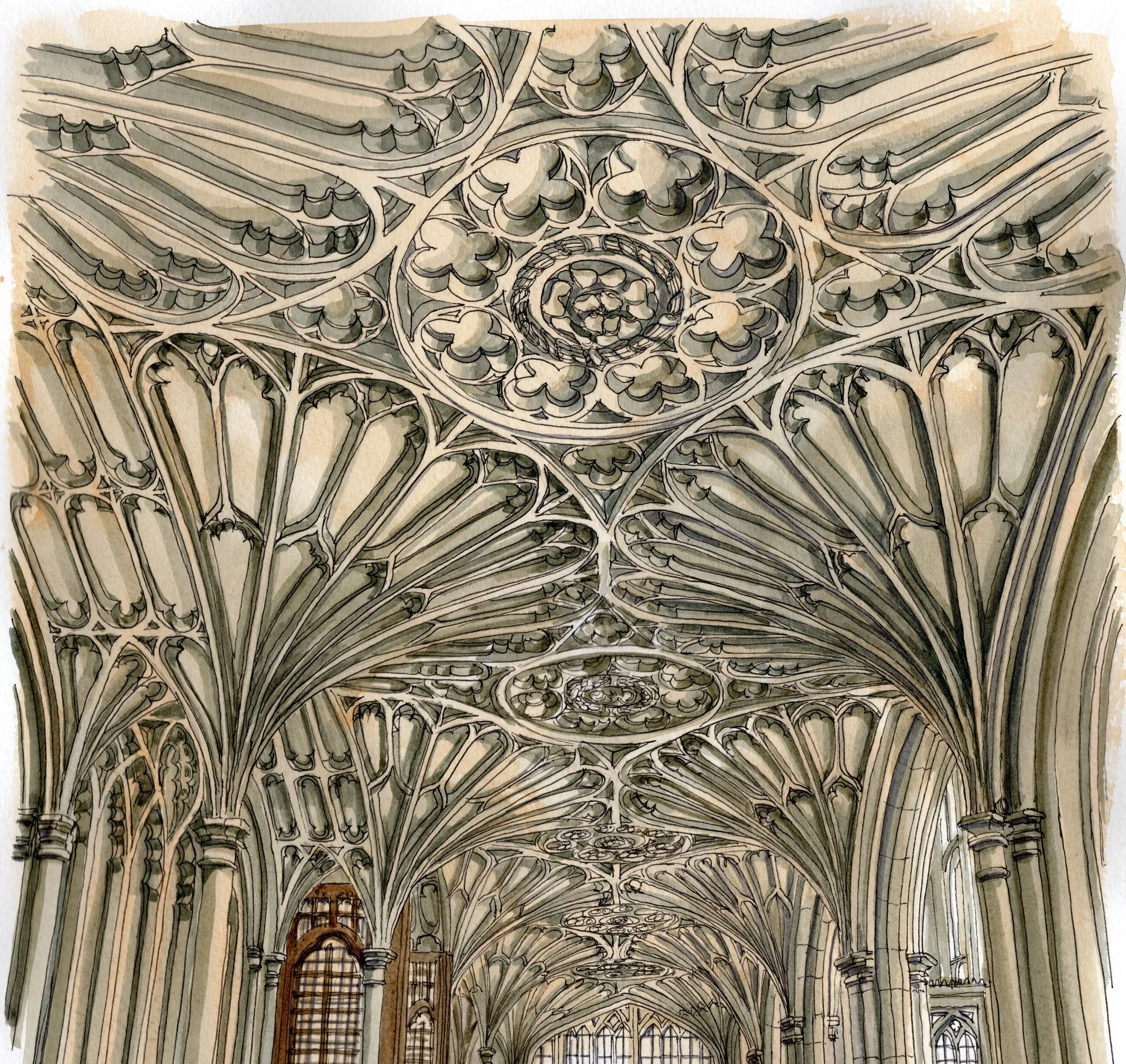

Betty Edwards, in her influential work on drawing and perception, demonstrated that the ability to draw isn't about having a "talent for art" but about learning to see. Her method, detailed in "Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain" (Edwards, 1979), teaches people to shift from the verbal, analytical mode of seeing (left hemisphere dominant) to the visual, spatial, holistic mode (right hemisphere dominant). It's essentially cognitive cross-training for perception.

Similarly, Kimon Nicolaides in "The Natural Way to Draw" (1941) emphasized that drawing is fundamentally about understanding form through sustained, intense looking—what he called "contour drawing" and "gesture drawing." Nicolaides wrote that the goal isn't to make a pretty picture but to develop an intimate, physical understanding of the subject. It's about training attention itself.

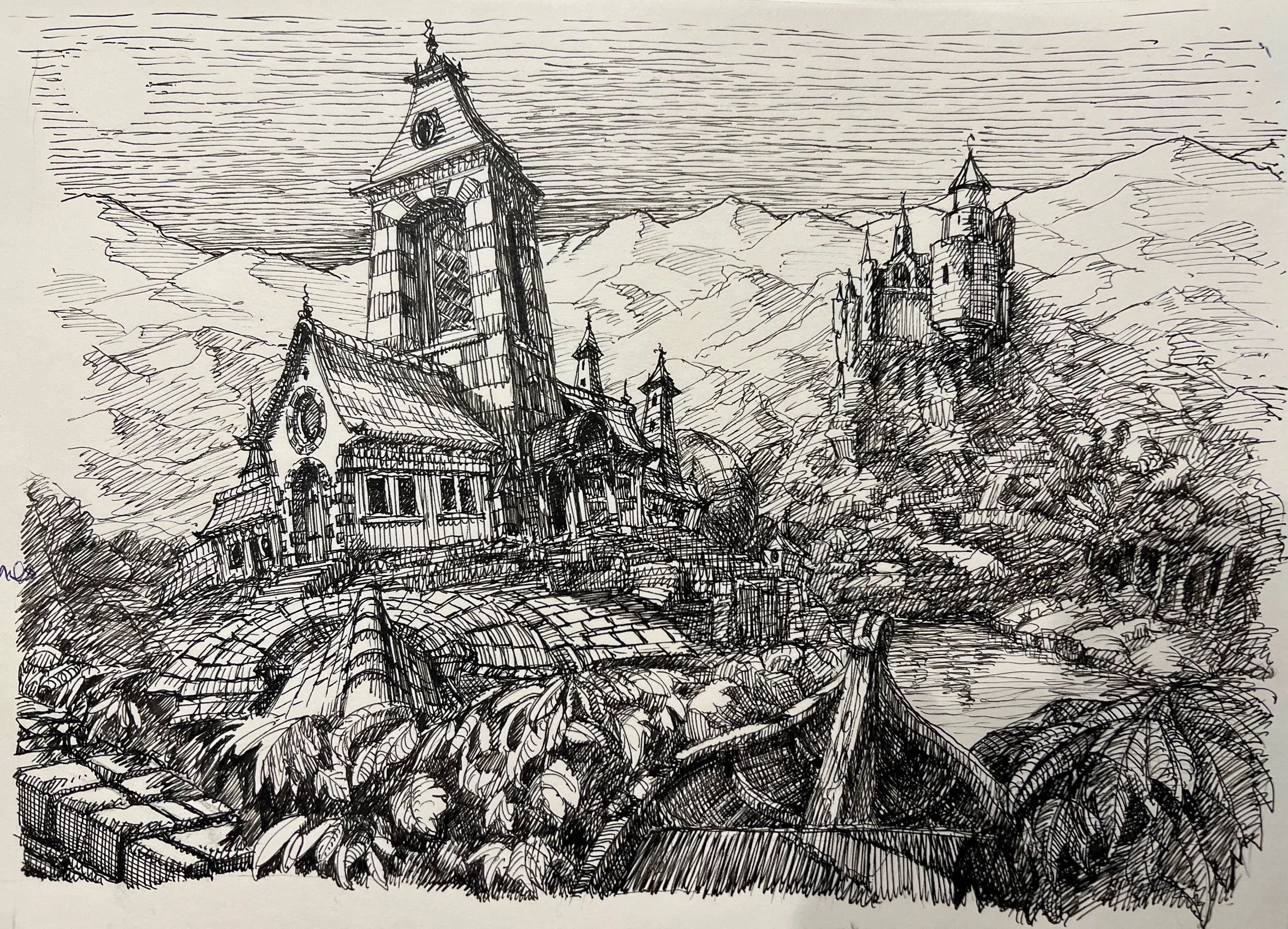

David Eagleman, a neuroscientist who has explored the brain's remarkable plasticity, notes that our brains are prediction machines constantly modeling the world. The designer's brain has been trained to question those predictions more aggressively, to look at a door handle and ask, "Why this shape? Could it be otherwise?"

Beau Lotto takes this further: our not seeing objective reality is essential to our ability to adapt and grow in uncertainty. If we could only perceive one fixed reality, there would be no basis for imagination. The designer's advantage is practicing this perceptual flexibility deliberately, systematically disrupting their own assumptions about how things should look, feel, or function.

Flow and the Focused Mind

Of course, creativity isn't all wild divergence. There's also the deep focus state that Csikszentmihalyi called "flow"—that condition where you lose yourself completely in the work, where hours pass like minutes and you're operating at peak capability (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Flow emerges when challenge and skill are perfectly balanced, when the task is hard enough to engage you fully but not so hard that you become frustrated.

Neuroscience has begun to identify the neural signatures of flow states, which involve a temporary deactivation of the prefrontal cortex—the brain region associated with self-consciousness and self-criticism. When you're "in the zone," you're quite literally out of your own way.

Sir Ken Robinson, the education reformer who championed creativity in schools, argued that our education systems systematically undermine this natural capacity for flow and creative thinking. In his viral TED talk and subsequent work, Robinson (2006) emphasized that creativity should be treated with the same status as literacy. He observed that we educate people out of creativity by teaching them that being wrong is the worst thing possible—when actually, creativity requires questioning assumptions and doubting what we believe to be true, which inevitably means risking being wrong.

The Physics of Insight: Richard Feynman's Playful Brain

Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, provides a fascinating case study in creative scientific thinking. Feynman famously approached physics problems with a childlike playfulness, often drawing diagrams that made complex mathematics visual and intuitive (his "Feynman diagrams" revolutionized quantum mechanics). In "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" (Feynman, 1985), he describes how he made breakthroughs by literally playing—watching plates wobble in the Cornell cafeteria and wondering about the mathematical relationship between the wobble and the spin, which eventually contributed to work that won him the Nobel prize.

Feynman's brain wasn't fundamentally different from other physicists'. What was different was his willingness to engage uncertainty playfully rather than anxiously, to pursue problems because they were interesting rather than because they were important. He was, in Lotto's terms, increasing his perceptual intelligence by taking agency in his own brain's process of making sense.

Recent Discoveries: Mapping the Creative Circuit

The neuroscience of creativity has advanced dramatically in recent years. A 2025 study published in JAMA Network Open found that creativity maps to a specific brain circuit centred on the right frontal pole, and damage to this circuit can both decrease and paradoxically increase creativity in certain neurodegenerative diseases. This helps explain why some individuals with frontotemporal dementia sometimes experience surges in artistic creativity as the disease progresses—damage to inhibitory circuits can release creative capacities that were previously constrained.

Research published in 2025 also showed that dynamic switching between brain networks predicts creative ability, suggesting that the creative brain isn't characterized by any single state but by flexibility—the ability to move fluidly between focused attention and diffuse exploration, between analysis and synthesis.

The emerging picture is one of creativity as a dance between multiple neural systems: the DMN generating possibilities, the executive control network evaluating them, the salience network directing attention, all coordinated by dynamic switching. It's not chaos, exactly, but it's not orderly either. Creativity just looks chaotic from the outside—it's actually a highly sophisticated form of logic moving through steps that are invisible to others.

Practical Implications: Designing for Uncertainty

Understanding the neuroscience of creativity has profound implications for how we work, teach, and design. If creative breakthroughs require us to embrace uncertainty rather than flee from it, then our work environments and educational systems need radical redesign.

Lotto's work with organizations emphasizes creating what he calls "perceptual intelligence"—the capacity to see differently and adapt to uncertainty. This isn't a soft skill; it's perhaps the hardest skill, requiring us to act against our deepest evolutionary programming.

For designers specifically, this means building in time for mind-wandering (engage that DMN!), practicing sustained observation (à la Nicolaides), deliberately shifting perceptual modes (as Edwards teaches), and creating conditions for flow (as Csikszentmihalyi outlines). It means treating uncertainty not as a problem to be solved but as the very medium of creative work.

Damasio's insights about the role of emotion and bodily states in creativity suggest that the "disembodied thinker" model is fundamentally flawed. You can't have creative breakthroughs while ignoring your body's signals. Creative work requires somatic intelligence—paying attention to gut feelings, energy levels, the physical experience of being stuck versus being in flow.

The Beautiful Paradox

Here's what the neuroscience tells us: the creative brain is not a special brain. It's a brain that has learned to leverage its own machinery more effectively, to harness the default mode network's wild ideation, to balance divergent and convergent thinking, to trust the body's wisdom alongside rational analysis, and above all, to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

Lotto puts it beautifully: nothing interesting begins with knowing; it begins with not knowing. Every creative breakthrough starts in that uncertain space where we don't yet understand, where the answer hasn't arrived, where we're willing to be wrong.

The designer's brain, then, is simply one that has made friends with this discomfort. It's a brain that has practiced seeing differently so many times that "differently" becomes a kind of home. It's a brain that understands, as Damasio teaches, that feelings aren't obstacles to clear thinking—they're essential ingredients. It's a brain that knows, as Feynman demonstrated, that playfulness isn't frivolous; it's fundamental.

Your next creative breakthrough is already forming in your default mode network, probably while you're doing something entirely unrelated to the problem you're trying to solve. The question isn't whether it will come—it's whether you'll create the conditions to recognize it when it does.

So the next time you're stuck on a problem, maybe stop trying so hard. Take a walk. Doodle. Daydream. Let your brain do what it does best: wander into uncertainty and, occasionally, stumble upon something brilliant.

After all, evolution gave you this magnificent prediction machine. You might as well use it to predict something interesting.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. HarperCollins.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Putnam.

Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt.

Damasio, A. (2018). The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures. Pantheon.

Damasio, A. (2021). Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious. Pantheon.

Eagleman, D. (2015). The Brain: The Story of You. Pantheon.

Edwards, B. (1979). Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. J.P. Tarcher.

Feynman, R. (1985). Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! W.W. Norton.

Lotto, B. (2017). Deviate: The Science of Seeing Differently. Hachette Books.

Nicolaides, K. (1941). The Natural Way to Draw. Houghton Mifflin.

Robinson, K. (2006). "Do Schools Kill Creativity?" TED Talk.

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything. Viking.

Recent Research Cited

Bartoli, E., et al. (2024). Default mode network electrophysiological dynamics and causal role in creative thinking. BRAIN, 147, 3409-3425.

Chen, Q., et al. (2025). Dynamic switching between brain networks predicts creative ability. Creativity Research Journal.

Kutsche, J., et al. (2025). Mapping neuroimaging findings of creativity and brain disease onto a common brain circuit. JAMA Network Open, 8(2):e2459297.