Metaphors Create Meaning

“Together on Eagle’s Wings”

Joe Biden, President Elect - USA

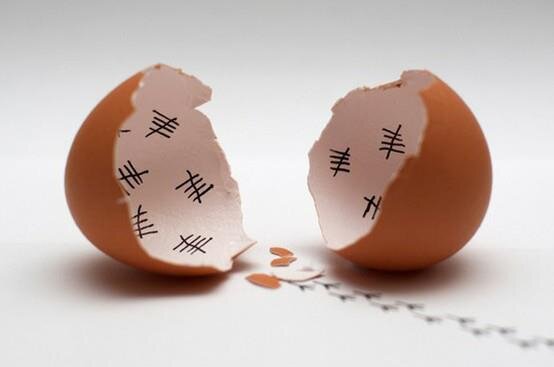

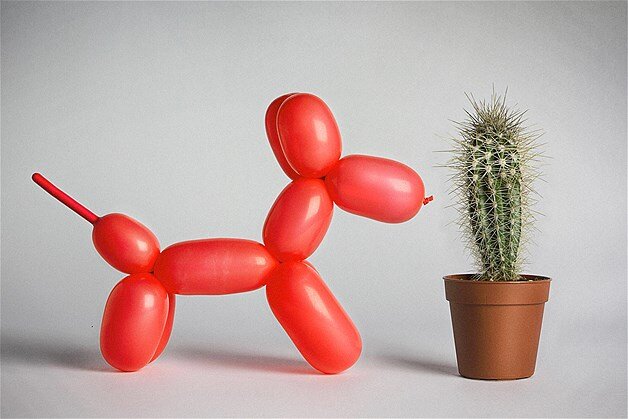

If I were to say; “my heart is broken”, you would know what I meant and your “heart may reach out to me” in sympathy. “I’m in pieces!” You’d get a pretty good idea that something had happened that had truly upset me and I was having difficulty coping with it and that perhaps you could help to “put me back together again”. Of course, I’d “bottle up my feelings”, which might suggest that at some point in the future all my feelings will explode into a “complete mess”. Everyday speech is littered with metaphors. It’s not just poets that use them. We use them in almost everything we say so that we can better express and communicate meaning more clearly.

Metaphors are essential for our understanding of the world and, most importantly for how we think. It is how our brains work and how we assimilate new knowledge, build communities, bind societies together, and inspire others to follow us or an idea. I believe that the use of metaphor is very closely related to creative and conceptual thinking. Metaphors infuse and color every aspect of our perception and interpretation of the universe we exist in. They shape our beliefs, our attitudes, and our actions.

Metaphor is a central aspect of human rationality.

George Lakoff.

Association and emergent properties.

Metaphors link two unrelated concepts or images together to form a new meaning that wasn’t evident from the original images. We use a metaphor to shed new meaning by conjoining familiar concepts to create a new concept. Our memories work similarly; we associate the object we wish to recall later with an object with which we are already familiar. We link concepts together. This is sometimes called the Method of Loci and was first mentioned by Cicero in the first century BC. This works by associating the thing we wish to recall with something already familiar to us with an image. The more vivid and visceral the imagined image and experience are, the easier it is to recall. Our brains work by associating concepts and ideas. However, metaphors take this one step further by creating a new meaning.

Metaphors take objective information from the outside world and hook them onto existing knowledge, experience, and memory to either reinforce what we already know or to create a new understanding, and, perhaps new knowledge.

However, metaphors do something else; they assist in forming our beliefs, how we see the world, and therefore how we behave.

In 2011, a Stanford study gave one group a pamphlet describing crime as a wild beast preying upon a city. A second group was given a different pamphlet describing crime as a virus plaguing the population. When asked how to tackle the issue, the first group were 20% more likely to endorse stricter policing than the second.

Framing.

Metaphors are so ubiquitous and familiar that they almost feel literal.

Time is a difficult concept to get our heads around, so we may say “Time is Money”, or “How did you spend your day?” These phrases reflect how our societies view time; we equate time with money. Or perhaps “Time flies”, “Time on my hands” is also a reflection of how we think as a society. Time is metaphorical. We are traveller’s on a path with our future ahead of us and the past behind us.

George Lakoff, the American linguist, called these orientational metaphors.

Lakoff also helped develop the idea of political framing. The words we choose directly affect how we understand and deal with social issues and steer us to decide what becomes common sense and received wisdom. Metaphors play a huge role in that.

Those people who get to impose their metaphors on the culture get to define what we consider true. Metaphors matter for what we believe and how we treat others and form our laws. Metaphors become our agreed way of framing our collective vision because, when they are effective, they create new meaning and therefore new purpose.

Revolutions start with words and strong metaphors. Metaphors are mental imagery and mental imagery is how we formulate our world view.

Truth

There is no such thing, objectively, as time flies. The brain does not actually behave as a computer. Nevertheless, these concepts help us to visualize a different truth. Metaphors are not true, but they do point to a truth, a truth that is connected to how we learn, assimilate information, and deeper understanding.

“Juliet is the sun-” is false, in the literal sense, but taken metaphorically it is not only true but sheds additional meaning on Romeo’s words. Metaphors become true if we list out the associated properties and if it deepens our understanding and meaning. Juliet does share qualities with the sun such as radiance, luminosity, and brilliance. She makes the day when she wakes up. There is an emergent property that is greater than the sum of its parts and the interaction of the two creates new meaning. That meaning and understanding were not available prior to the metaphor.

We use metaphors to explain something we don’t understand with references to things we do understand. This is the creative process in action; finding new associations between things that may not previously have been associated together. In the creative process, we find ways to solve problems by using diverse knowledge and re-assembling them into a solution. Truth is a correlation between reality and knowledge - and metaphors give us a way to perceive and to understanding.

Hegel called this Conceptual Borrowing. It revised our perception of the world. We see the world subjectively and therefore our perception of the world is about the relationship between different subjective perceptions that makes new concepts. Metaphors are the means by which the textures, ambiguities, and complexities of experience can be articulated. They revive our perception of the world through which we become aware of our creative capacity for seeing the world anew.

Metaphors advance with knowledge and understanding.

Knowledge advances in parallel with our technology and understanding of the world. The two work hand-in-hand.

The ancient Greeks conceived the brain and body in relation to their knowledge and technology at the time. They conceived the body as grounded in the technology of the water clock. Hippocrates defined them as the four humors: black bile yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. Galen linked them to temperaments: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic. The nerves conveyed animal spirits between tissues dominated by the humors.

Weight-driven clocks were developed in the 13th century and Pendulum clocks appeared in the 17th century, they served as metaphors for understanding the brain and its functions.

Descartes in the 16th and 17th centuries advocated a mechanical account of the physical universe and living organisms. Only the human mind was excluded as being of a very different substance. The nervous system transported animal spirits to and from the brain.

Hobbes, the English philosopher, said that ideas and associations result from minute mechanical motions in the head. In “La Mettrie in L'Homme Machine” (1748), he wrote the human body as "a machine that winds its own springs”.

Jacques de Vaucanson’s (1739) mechanical duck, was created as an entertainment piece. Although biological organisms are not composed out of metal parts, the idea that they are machines captivated many biologists. Cells in this era were viewed as factories with different organelles performing different tasks.

Electricity, at first a curiosity, seen in Galvani’s and Volta’s pioneering research in the 1790s with the development of the galvanometer, measured electric currents in animals and began to shape a new concept of the functioning of the brain and body.

Helmholtz progressed this concept further by measuring the speed of electrical transmission and linked nerve electricity with chemical processes involved in the generation of action potentials (sparks between synaps’) at the beginning of the 20th century.

In the 19th century, Charles Babbage designed the difference engine to tabulate polynomial functions (only actually built in the 20th century). World War II provided incentives to perform complex calculations quickly, leading to the creation of ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, commissioned in 1946). Subsequently, devices that employed stored programs led to the beginning of the concept of a computing mind with memory storage.

In the 20th century, the first microscopic images of neurons emphasized their axons and dendrites. Helmholtz developed the telegraph metaphor for the functioning of the organic brain.

Hodgkin and Huxley borrowed the mathematics developed for signal propagation in wires, to model the generation of action potentials, and the telephone switchboard model of brain activity gained currency.

Turing further developed the idea that the human activity of calculation was computation. The Turing Machine metaphorically extended the metaphor of applying rules to symbols on paper to a machine and then to the brain.

Boole articulated the idea that thought consists of the application of rules to symbols. With the advent of computers in the 1950s, this was applied to an understanding of how we think.

Newell and Simon’s Logic Theorist served as an exemplar winning the world chess championship. While especially prominent in cognitive science, the idea that the brain computes became attractive to parts of neuroscience. The idea of a central processor manipulating symbols seems problematic. Rather, theorists often view individual brain areas as computing functions.

Pitts and McCulloch (1943) proposed that neural networks could implement logic functions. They and others soon came to focus on combining information in ways not dependent on logic.

Finally, we have advances in neuroscience, the internet, and the world-wide-web which has stimulated the conception of the brain as a complex neural network; a three-dimensional interwoven network of connections.

We don’t know or understand how the brain creates conscious thoughts, but each technological step forwards refines and reframes our concept.

Political Framing

All language transfers meaning from one person to another. The power of language and the concepts behind it have the ability to mobilize and galvanize people in political movements. It’s language that creates revolutions and the strength of the embedded metaphors is often the agent of action because of its synchronicity with how we think and the truth that a strong metaphor delivers.

Leaders mobilize people not just by their words and their passion, but by the concepts that drive their thinking. That thinking is delivered by the strength of their metaphors.

Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world.

Nelson Mandela.

Aggression unopposed becomes a contagious disease.

Jimmy Carter

A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on.

John F Kennedy

“It is a mistake to try to look too far ahead. The chain of destiny can only be grasped one link at a time.”

Winston Churchill

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

Winston Churchill

You may also be interested in: Metaphorical thinking. One thing in the context of another